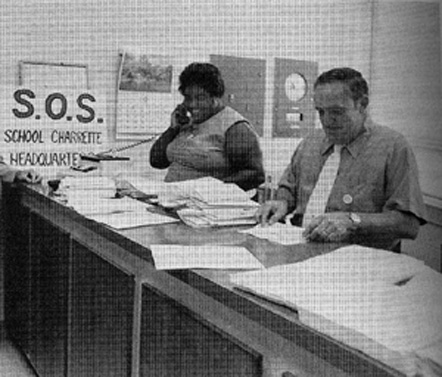

Ann G. Atwater & Claiborne P. Ellis, School Integration Charette Leaders

Ann Atwater and Claiborne P. Ellis had much in common, although it would take years of battling each other across the racial divide before they were able to see their similarities. Atwater lived in a dilapidated house on an unpaved street in Durham’s Hayti district, where she struggled to support her two daughters. Ellis lived across the tracks in a neighborhood nearly as destitute, but white. He worked multiple jobs to support his family, but like Atwater, he barely found the funds to make ends meet. The two were fiercely dedicated to improving the prospects of “their” people, Atwater as a militant activist for housing reform, and Ellis as the Exalted Cyclops of Durham’s Ku Klux Klan. Ellis’s position at the margins of white society frustrated him, and looking for a scapegoat, he turned to the target provided by the Klan, as he explained in a 1980 interview with oral historian Studs Terkel:

I really began to get bitter. I didn’t know who to blame. I tried to find somebody. I began to blame it on black people. I had to hate somebody. Hatin’ America is hard to do because you can’t see it to hate it. You gotta have somethin’ to look at to hate. The natural person for me to hate would be black people, because my father before me was a member of the Klan. As far as he was concerned, it was the savior of the white people. It was the only organization in the world that would take care of the white people. So I began to admire the Klan.

Ellis found his voice in the Klan, and rising to become the its local leader, he began to take the Klan in a new public direction. As the civil rights movement increased in urgency and militancy, he believed acting as a spokesman on behalf of the Klan was crucial to upholding the “Southern way of life” and its “natural” social hierarchy. Conservative town leaders were largely receptive to his message.

In the 1960s, eighty percent of black Durham residents lived in substandard housing, a figure which had remained unchanged since the 1920s. The Housing Authority, part of an old boy network headed by autocratic cotton mill executive Carvie Oldham, failed to enforce housing codes. Any discussion of the matter ended bogged down in a bureaucratic cycle of “commissions, committees, councils, boards of inquiry, official investigations, delegations, panels” – a endless “substitution of talk for action.” Atwater, emboldened by community organizer Howard Fuller, discovered a passion for housing reform and a natural talent for leadership first with Operation Breakthrough, then as chairwoman for the United Organizations for Community Improvement. She organized her community to rail against the city’s repressive and reprehensible policies towards black housing, often peacefully in pickets and marches and city council meetings, but she was not averse to more violent tactics, as when she participated in the bombing of the Housing Authority.

The two were thrown together in 1971 as co-chairs of a charrette, a series of long and intense meetings between a diverse group of people. The purpose of this charrette was to discuss school desegregation, a still contentious issue, and to draw up a series of recommendations to present to the school board. Considering their history of mutual animosity, Atwater and Ellis were reluctant to work with the other, but both knew that to have their opinion represented, they must participate. It was during this series of meetings in the summer of 1971 that C.P. Ellis began to change. Sitting down with his nemesis, he realized that his struggles were her struggles too, and that they shared a fundamental commonality of experience. Ann Atwater, in an interview with the Carolina Times, expressed this sentiment:

Mr. Ellis has the same problems with the schools and his children as I do with mine and we now have a chance to do something for them. There certainly is no deep seated love between Mr. Ellis and myself but this school project brings out problems we all have. We are going to have to lay aside our differences and work together. This will be the first time two completely different sets of philosophies have united to work for this goal of better schools. If we fail, at least no one can say we didn’t try.

Change did not come easily or suddenly, and the two faced ostracism, even death threats; C.P. Ellis had an especially difficult time returning to his life post-charrette, as he had “lost his effectiveness in the conservative community,” which he acknowledged in a toast on the last night of the charrette. Ultimately, the school board disregarded the proposals put forth by the charrette, but the friendship C.P. Ellis and Ann Atwater established during that time endured, as did Ellis’ change in attitude. He went on to organize labor unions for both blacks and whites. Ellis and Atwater spoke together about their experience at events around the country, and at C.P. Ellis’s funeral in 2005, Ann Atwater delivered his eulogy.

Back to Category